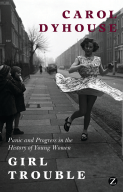

Girl Trouble:

Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women

Carol Dyhouse

Book Review

Girl Trouble is an outstanding history of the lives, status, and representation of young women in Britain from the 19th century until the present day. It is a book founded upon an extraordinary range of source material – from 0police files to autobiographty, documentary film to government report – and underpinned by an intimate an wide-ranging understanding of the past. In fact the book is a model of how to write history that matters for an audience that cares: it will undoubtedly be widely read and enjoyed. The book builds upon Carol Dyhouse’s extensive prior academic research into young women, education, and popular culture, but is clearly aimed at an audience beyond, as well as within, the academy.

Girl Trouble is an outstanding history of the lives, status, and representation of young women in Britain from the 19th century until the present day. It is a book founded upon an extraordinary range of source material – from 0police files to autobiographty, documentary film to government report – and underpinned by an intimate an wide-ranging understanding of the past. In fact the book is a model of how to write history that matters for an audience that cares: it will undoubtedly be widely read and enjoyed. The book builds upon Carol Dyhouse’s extensive prior academic research into young women, education, and popular culture, but is clearly aimed at an audience beyond, as well as within, the academy.

Carol Dyhouse’s writing is both compelling and economical: incisive analysis is delivered in engaging prose throughout. Early on in the book, for example, she tells us that ‘In reality, girls travelling alone in the 1900s were much more likely to be accosted by social workers determined to protect young innocents than by pimps or predators’, delivering in one short sentence a sharp assessment of the early 20th-century ‘White Slavery’ panic (which saw the generation of public outrage through the publication of often prurient accounts of ‘respectable’ white women kidnapped and sold into sexual slavery). Elsewhere we are informed that ‘It wasn’t just columnists in the Daily Mail who were likely to hint at a connection between confectionary and immorality’ (p. 93). The lightness of touch here underlines the bizarre ways in which young women’s consumption choices have been – and often continue to be – read. The pace of the book is beautifully judged throughout. Major shifts are illuminated through just the right use of detailed example – historical depth is delivered with consummate ease. Crucially, the story of modern girlhood is delivered with consistent good humour and an eye for the telling story.

The book opens amidst the aforementioned White Slavery panic of the late 19th and early 20th century and ends amidst the ‘sexualisation’ panic of the 21st century. Along the way, we see the extensive efforts made by a range of interested parties to restrict young women’s opportunities and to crush their assertions of independence. In a discussion of educationalist opinion in the aftermath of the Second World War, for example, Carol Dyhouse outlines the views of eminent writer Sir John Newsom: ‘Girls needed fewer books and should be taught more cookery so that they could cosset their future husbands. Men cared very little for erudition in women, Newsom pontificated, but they did enjoy a good dinner’ (p. 127). Decades earlier Robert Baden-Powell had reacted to the emergent ‘Flapper’ with horror: ‘Not until the next generation is born shall we know the full extent of the mischief that these restless young girls, craving to draw attention to themselves, are doing to the race’ (p. 78). At the end of the 20th century the ‘ladette’ emerged as the folk devil of choice amongst the popular press.

And yet within this book the diverse ways in which young women challenged and subverted patriarchal attitudes is also consistently apparent. At the heart of this book we find a cast of powerful characters who engaged with the world on their own terms. Figures such as Queenie Gerald, a woman deemed so dangerous that young police officers were not to be left alone in her presence, or the ‘baby Suffragette’, 16-year-old Dora Thewlis sent to Holloway Prison for attempting to rush the House of Commons in 1910. We meet the ‘brazen flappers’ and modern girls, castigated for their pleasure seeking – as if pleasure seeking was in of itself an immoral transgression. We meet the ‘good time girl’ – ‘no better than she ought to be … likely to wear cosmetics and cheap perfume, and to dream of owning a fur coat’ (p. 107). Predictably, she too became a folk devil. We encounter the darkness of the ‘Cleft Chin’ murders perpetrated by a 17-year-old girl and her American GI boyfriend, alongside the optimism of ‘Millions Like Her’ girl Betty Burden presented by the magazine Picture Post as a beacon for the future. As Carol Dyhouse concludes, ‘Girl’s behaviour has regularly been judged as innocent or corrupt, white or black, with no shades of grey in between. A consequence of this has been a tendency to portray girls as either victims or villains rather than ordinary, curious, fallible human beings’ (pp. 250–1).

And in amongst the stories of individual triumph and societal disapproval is a very clear narrative of significant social and cultural change over time. The book does not shy away from the big issues that have confronted feminism – and young women – across the 20th century and continue to preoccupy into the 21st. The tension between victimhood and agency within feminist writing is consistently addressed. However, the book does, ultimately, make an optimistic case for improvement across time, founded in the capacity for young women to determine their own lives and drive social change. Girl Trouble starts by asking ‘Are girls better off today than they were at beginning of the twentieth century?’ and concludes that they probably are. This is not an uncritical progress narrative, but it does show the value of the long view to contemporary debates.

Review ©2013 Claire Langhamer, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women is published by Zed Books

Review originally published in Gender & Development 21.3 (2013)