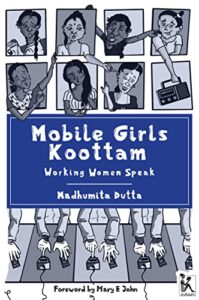

Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak

By Madhumita Dutta (illustrated by Madhushree), New Delhi: Zubaan Publishers, 2021

Reviewed by Padmini Swaminathan

The discipline of Women’s Studies has pioneered several methodological innovations to, among others, capture women’s voices, visibilise women’s work, examine and interrogate the assumptions of mainstream (largely androcentric) disciplines, apart from battling with data-collecting agencies, national and international, to document ‘work’ in its entirety rather than just ‘paid or gainful’ employment. The book under review goes a step further in this methodological innovation by inviting readers to ‘listen’ to working women conversing among themselves on a range of topics – joints and places that are ostensibly ‘public’ but not quite so for single women; the trauma that accompanies menstruation be it at home or the workplace; the perception of the futility of specific work experience gained in the making of a product with the imminent threat of the factory closing down and no alternative job in sight except the inevitability of marriage looming at the end of the road.

The discipline of Women’s Studies has pioneered several methodological innovations to, among others, capture women’s voices, visibilise women’s work, examine and interrogate the assumptions of mainstream (largely androcentric) disciplines, apart from battling with data-collecting agencies, national and international, to document ‘work’ in its entirety rather than just ‘paid or gainful’ employment. The book under review goes a step further in this methodological innovation by inviting readers to ‘listen’ to working women conversing among themselves on a range of topics – joints and places that are ostensibly ‘public’ but not quite so for single women; the trauma that accompanies menstruation be it at home or the workplace; the perception of the futility of specific work experience gained in the making of a product with the imminent threat of the factory closing down and no alternative job in sight except the inevitability of marriage looming at the end of the road.

The author’s curiosity to comprehend the motivations of young, generally unmarried, women’s entry into new manufacturing sites, and their perceptions of what such work (that took them away from their village homes) meant to them, led her to eschew received wisdom on how academic literature has generally used ‘narratives’ to portray such work. Rather, by reproducing the (translated) conversations that she and her friend cum field interpreter, Samyukta, have documented, we get a flavour of how the conversations have flowed without being structured. While readers are ‘invited’ to listen, meaning-making of the conversations ceases to be the prerogative of the author alone in such a methodology. Madhumita has penned an extremely brief chapter, ‘Reflections’, at the end, but the conversations lend themselves and are amenable to far more and sometimes very diverse types of interpretations than that offered by the author. This review attempts to add to the author’s ‘Reflections’.

The book introduces us to the five women whose conversations among themselves and with Madhumita and Samyukta form the subject matter of the book. These women come from different districts of the southern state of Tamil Nadu, India, and they belong to diverse caste backgrounds and their families engaged mainly in farming. Employed in an electronics factory for four to six years, all these women had ‘formal written contracts, regular wages, and benefits such as maternity leaves, provident funds, Employees State insurance, and so on’ (p. xxi). Interestingly, in their conversations over the imminent closure of this factory, one of the women, Kalpana, notes:

I think it is a big deal to work for such a salary with these qualifications, because today even graduates or doctorates find it very hard to get a job. So, with twelfth standard qualifications … to get ten thousand rupees … It is hard to get a job like this. People are working so hard for salaries as little as five or six thousand rupees. (p. 164)

Nowhere in the conversation is the question of the terms and conditions of the formal written contracts discussed nor does it form part of the ‘Reflections’. More importantly, the fact that women formed 60 per cent of the permanent workforce of the factory calls for a discussion of, not only why these women were preferred but also given a permanent status, when elsewhere, in other industries, it is common knowledge that more women than men are denied appointment letters, more women than men are not recognised as workers and therefore became ineligible for any worker-related benefits.

The conversations have been brilliantly organised to enable readers to get to the heart of the matter immediately. Thus, for example, the discussion over and about tea-making quickly veers towards why roadside tea shops – otherwise public spaces – are not spaces that make women, particularly young girls, comfortable. There is much discussion about how socialisation happens in households to ingrain in girls why public joints, which men freely visit, individually or collectively, become socially taboo for women. It would have been interesting if the author had gone further and reflected about how this conversation compels us to relook at our received notions of what constitutes ‘public’ and how do some of these ‘public’ spaces become different for men and women.

The conversations over the theme of menstruation that span across several chapters in the book are very instructive. They seamlessly combine social, cultural, religious, medical, and work-related aspects, along with highlighting how little useful knowledge is actually imparted, either in school or households, on what is otherwise a routine biological function. The women’s description of their first period, their confinement for a considerable period of time in an isolated space, the elaborate and expensive rituals that accompanied their attainment of puberty, and the restrictions on their mobility and communication with boys that followed thereafter, is an eye-opener in many ways. Firstly, with minor variations, what emerges is that the practices associated with menstruation cut across caste and region in Tamil Nadu; secondly, anxiety among parents builds up as soon as girls attain puberty since rural society in particular considers menstruating girls as ‘ready’ for marriage; thirdly, the conversations bring out how young girls, socialised into treating menses as a taboo topic for open discussion, ‘adjust’ to the situation among themselves, and find that they are unable to request their supervisors to either allow them to visit the washrooms or rest when experiencing excruciating menstrual pain, even while admitting that their supervisors would ‘understand’ only if they opened up to them; and fourthly, as sanitary pads have replaced cloth, the conversation around how pads are dispensed by shops is truly insightful:

In the medical shops, for their business and advertisements, they display pictures of sanitary napkins. So many people walking on the road … all of them see it. It doesn’t disturb them to see it.

But when a girl goes to the shop and asks for sanitary napkins, they wrap it up in a newspaper and put it in a plastic cover, as if it is something that shouldn’t be seen, as if it should be hidden. (p. 113)

Equally insightful are the descriptions of what happens on the shopfloor, how line departments are organised, incentivised, and goaded to produce more. The announcement of the imminent closure of the factory was a bolt from the blue for the girls who had completely identified themselves with the factory and their work:

In the China factory, it took them fifteen years to achieve the target of five hundred million … We achieved five hundred million in five years! Then can you imagine how hard we have worked for this? And now how arrogantly they are saying that they will let go of two thousand of us? The Chennai factory earned the most profits for Nokia. Today they call us ‘excess manpower’ … If need be get more orders to match the manpower. Please don’t tell us there is excess manpower because you don’t have orders today. (pp. 158, 165)

An important aspect discussed by the girls but not reflected upon by the author is the theme of what constitutes ‘work experience’. To quote one of the girls:

What can we do with the experience of working here in other companies? If you are going to a company that makes something else, what is the relation between mobile phones and that? So, even though we have so many years of experience here, it is a waste, right? (p. 169)

Literature speaks of how companies/industry organisations need to invest in upgrading skills of workers. The conversation in the book compels us to think about what skills are to be imparted when a factory closes down; workers and their experience are rendered redundant when there is no other factory producing a similar product for their experience and skills to be of use.

In sum, this book is a seminal contribution to the Social Sciences, methodologically and otherwise. Approached from any discipline, it is an invitation, not just to ‘listen’ but also to read between the lines and questions one’s own received knowledge on a number of themes. The rich contents emanating from the conversations warrant a far more engaged and in-depth ‘Reflection’ than that provided by the author.

© 2022 Padmini Swaminathan